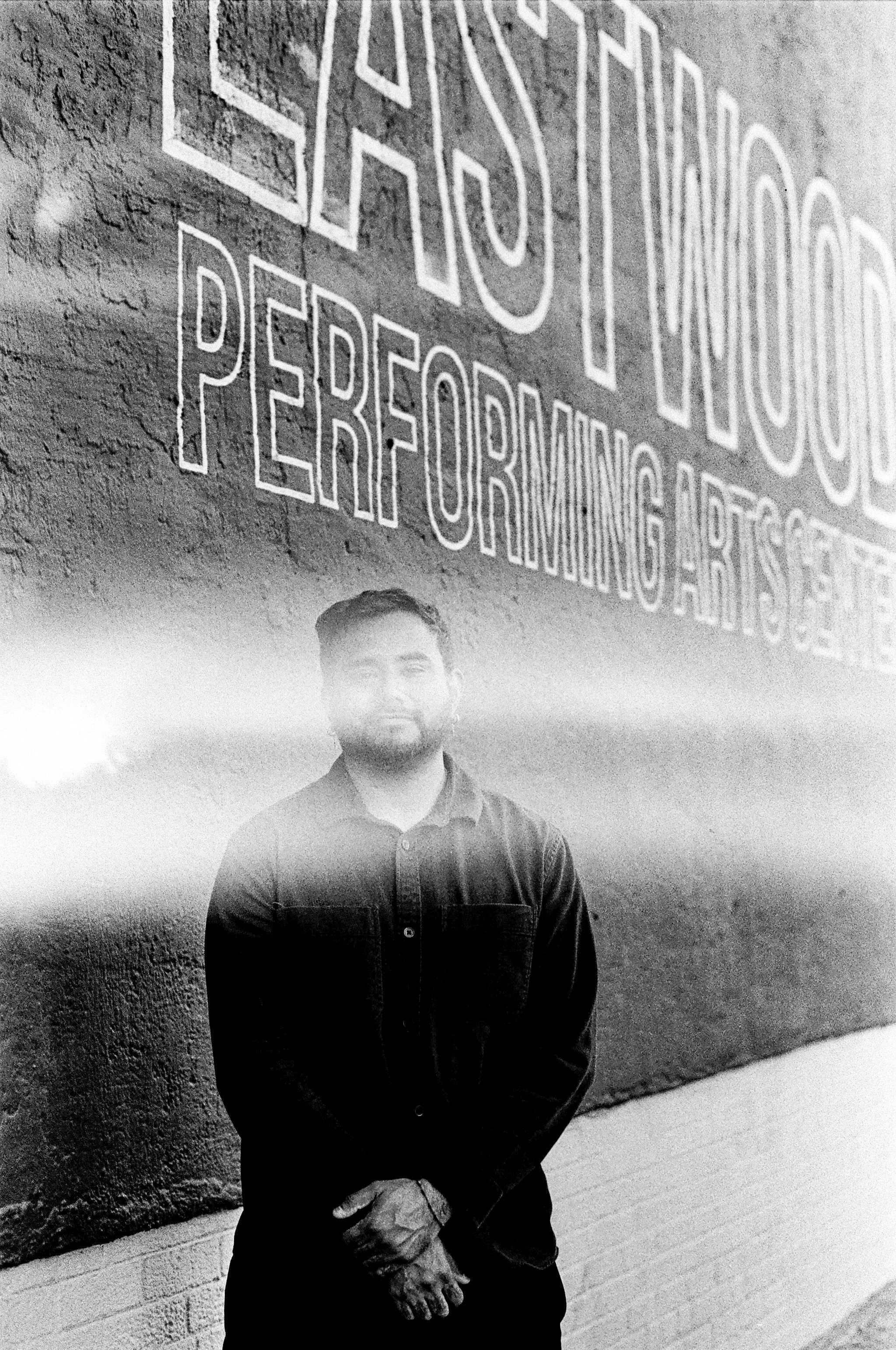

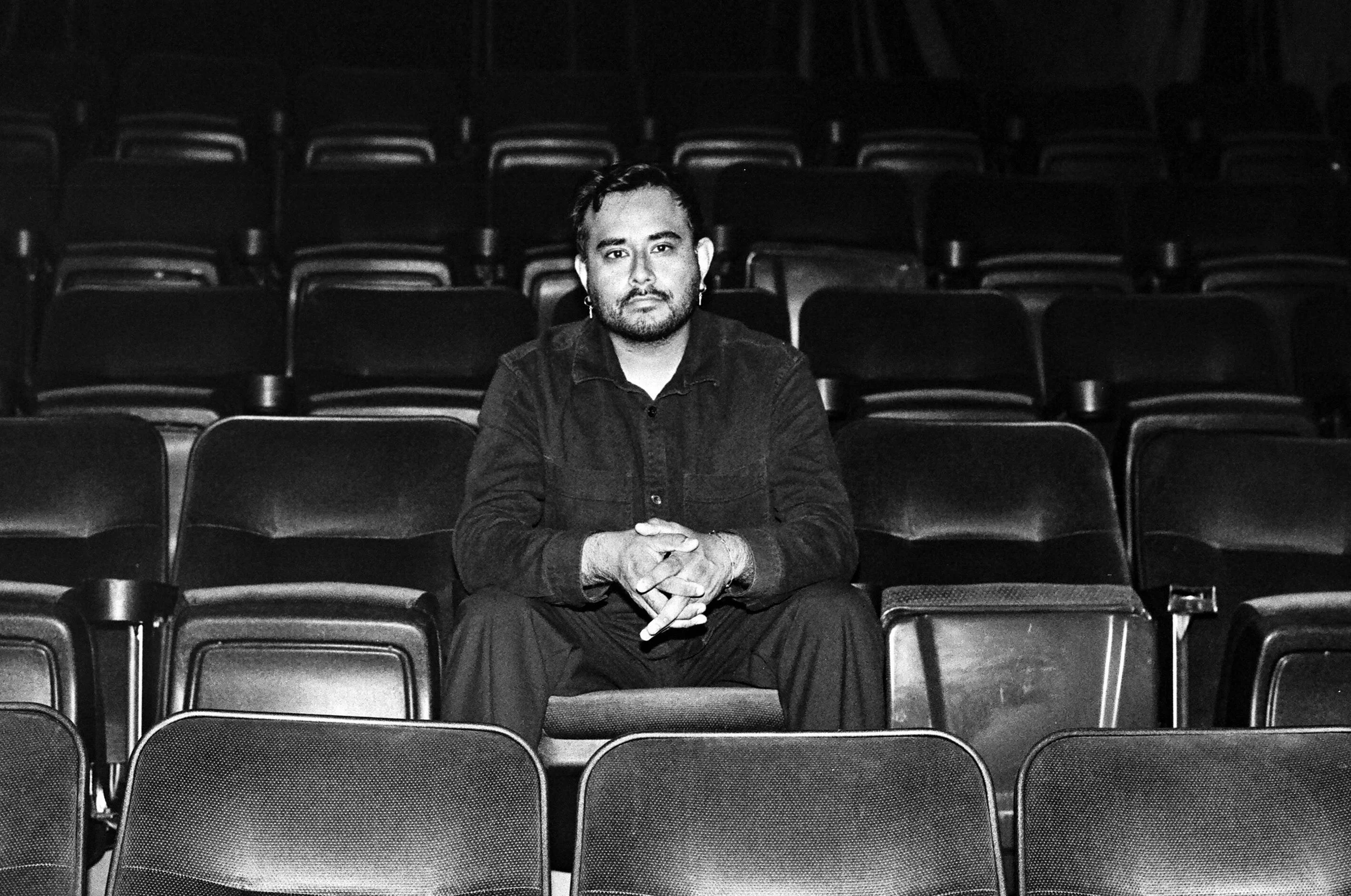

Omar Salas Zamora

by Patrick Peña

June, 2024

This interview was originally published in Luchastyle Issue 1 (June 2024).

It has been condensed from its original printing. The full uncut version is available for purchase [here].

Omar Salas Zamora is a filmmaker from Los Angeles.

It’s a beautiful Monday evening when I sit down to talk to Omar. Unfortunately, not in person, as I am in the small town of Sumner, Washington and can’t make it down to Los Angeles, where my subject, filmmaker Omar Salas Zamora, is hard at work, having just opened The Eastwood in Hollywood, and is in the process of developing his next feature film. Coming off of the hits Here Comes Your Man and Adam in Fragments on the streaming service Dekkoo, he has just finished post-production his latest film The Prodigy, a sequel to Adam. But he was able to find the time to talk about Lloyd Kaufman, 70s movies, representation and The Prodigy.

PA: Before every movie, you read “Make Your Own Damn Movie” by Lloyd Kaufman. Do you read it to be inspired all over again, or do you think there’s something new to learn every time?

OSZ: I think there is something to learn because I’m working with different budget levels, different levels of creativity and talent, and personalities. And that book so clearly explains, “if you’re dealing with this kind of person, do this.” And obviously a lot of it is a joke and you shouldn’t take it word for word, but there is a really great lesson to be learned for so many different kinds of situations. There’s such a melancholy in the second half of the book. “I’ve done all of these things, and I’ve shown you how to do everything that I do.” And he’s hanging out in the New York office walking around seeing all these posters in his leaking basement wondering, “what is all this for?” And it’s a very sobering reminder to remember to have fun when you’re having fun. It’s important to remind myself when you’re going onto a movie, because it’s extremely stressful and it’s extremely frustrating, and when it’s over you’re happy, and then three months later you’re like “I wish I was in that mindset again.” You have all these cylinders firing off at 1000% creativity when you’re making a movie. There’s very few times in life when you’re under that kind of pressure.

Sometimes you have to remind yourself why you’re doing it to begin with. “Art for art’s sake.” Which begs the question, what is it that you led to choose filmmaking at your method of expression? Why choose this medium over other forms of art?

When I was in high school I tried learning every instrument I could get my hands on. I tried being a musician. I thought filmmaking was too expensive. I loved movies as far as I could think back, I loved stories, I loved writing but it just felt like that is not possible, that is not within arms reach to me. So I tried writing songs, I tried playing music and I was not good at it. And I started realizing “Okay, I’m writing this kind of song because I want to shoot this kind of music video for it.” Then I realized I’m not writing a song to write a song, I’m writing a song so I can put a camera in my hand, so I can have something to shoot.

If I’m doing this kind of reverse engineering just to get to filmmaking why am I doing that to myself? Obviously it’s going to be extremely hard to be taken seriously as a filmmaker, but once that switch happened, I was a filmmaker. I’ve always been very confident with saying I’m a filmmaker. The hard part is convincing other people you’re a filmmaker.

Right. Now, with Here Comes Your Man, if I’m not mistaken that was the first real personal thing that you wrote and you weren’t sure if it was the kind of thing anyone would want to make, and then it became one of the first things people did respond to.

Yeah, I loved the idea of ‘the first episode they’re going to meet and the last episode they’re not going to see each other again.’ And that was the idea for the first season, really doing this kind of like Scenes From A Marriage, like a short film of this period of time in their relationship and a short film of that period of their relationship. And once I figured out I could break it into these five short films, that also just became the structure for a TV show. And I really liked that, that’s what was most exciting to me. And I never really wrote it thinking about an audience, but I did know that this was going to be the biggest audience that has ever seen any of my stuff. But it did get a positive response, and it’s nice to see over time, people on instagram and TikTok sharing it, some videos getting millions of views, that was the first time I realized, “there was an effect here.” This mattered to people. In Season 2, Alejandro’s monologue in the car was shared like crazy. And I worked really hard on that scene, to really make sure it rang true. And it’s really nice to have a project where your intentions are taken exactly how they were intended.

You feel understood.

Yeah, people reacted the way you wanted them to react. And that was a huge gift that Here Comes Your Man gave me.

If somebody wanted to refer to you as either, or both, a gay filmmaker or a Hispanic filmmaker, do you find that reductive, or do you feel a duty to represent the groups to which you belong?

I don’t feel a duty to represent anyone, but I do think in business situations where I’m approaching someone for financing, I’m absolutely not above saying “My name is Omar Salas Zamora, I’m a gay Hispanic filmmaker.” But, what you want to do is get in that room but once I’m in that room I’ve had very difficult conversations with a lot of companies, where they want me to write a certain thing and it’s like “well that’s not 100% exciting to me. But how about I give you this script that is actually very good, maybe it’s not checking the box that you want to but isn’t hiring me enough?”

What is it about 70s films that captures the spirit of what you’re trying to do as opposed to other decades?

There’s just such a freedom in that period of time, and there’s just, everyone is so raw. We had such great character actors. Even huge stars were character actors and that’s just something we see so little of now. In that period of time, you could have exploitation, you could have heart-wrenching drama, and there was just a feeling of “let’s see what sticks” to a lot of projects. And by the grace of God, or luck or whatever, 95% of them stuck. Even in movies that I don’t really love, there’s a kind of risk-taking that I just simply do not see anymore.

Yeah, there’s something about 70s films, even your standard 70s film somehow feels better than an average movie from any other decade. Is it because everything’s real? Like you said, real actors, stunts are real, everything’s for real. Everyone has to put their full passion into it.

Yeah, and back then, there was still this idea of the director or writer as a rockstar. One of my favorite writers of all time is Richard Matheson. He wrote Duel for Spielberg and a movie I really love called Dying Room Only with Cloris Leachman—on top of a shitload of so many other projects. And as great of a writer as he is and after writing major films like The Omega Man, he was still willing to take on something smaller and playful, like Duel. Whereas these are things I don’t really see from someone who is career-oriented in Hollywood now. I don’t see Greta Gerwig going back and making another Frances Ha.

No, Raimi doesn’t go back. Nobody goes back and makes their indie movies anymore even though they have the capital to do so.

Yeah. Something fascinating about [Peter] Bogdanovich: he made Paper Moon, What’s Up, Doc?, and The Last Picture Show back-to-back-to-back, then took a big swing with Daisy Miller, which was this big period piece that didn’t do well. So he immediately goes to the Philippines and made Saint Jack with Roger Corman money—a film about a guy navigating the world of prostitution. It’s so grungy and weird. You just don’t see directors taking risks like that anymore. Then the big shift happened in the late ‘70s when Variety started publishing weekend box office numbers. That completely changed the conversation around success. Now, it’s all about “Are you winning or losing?” whereas in the ‘70s, the focus was more on “Who made the better movie?”

Right. It’s become completely commercial. Now, many 70s films and your films have something in common, and that’s bittersweet endings. Your last few films have somewhat sad or downer endings, is that coincidental? Or do you always aim for an emotional ending? Is that your style?

I think with Here Comes Your Man I was thankful for the second season because I did feel that we wrapped it up in a much more positive way. Because when the first season came out and people reacted to it, and they really loved it, I almost felt guilty that it ended on such a down note, because now I saw people were affected by it I almost felt a personal responsibility for making people sad. Which is not something you feel on a large scale usually, so with season 2 I was really trying to find a way to solve that, and I think I did. But with The Prodigy, I think I was mostly wanting to do what people expect the least.

I think a lot of people will be surprised with what happens in The Prodigy. But at the same time, I think considering how Adam in Fragments ended, and how dark the story had become, I think a lot people will expect a much darker journey. How did the producers feel when they received it?

I get so little feedback from the producers on anything that I do, which I’ll take as a compliment. With The Prodigy they had a few notes, mostly tonally, and these are just suggestions, I’m sure they’ll take the movie however I feel is best. I think most people expected something a little sexier from Adam In Fragments, maybe something that caters to that audience, which is, you know, gay men. But I think that Adam became so dark where there’s not a lot of opportunity to have this actual sexy erotic scene. It just doesn’t call for it. Even if you terribly wanted to include that in the movie, the mountains you’d have to move narratively to make it happen would be insane.

There was definitely a big initial shock for The Prodigy. They were like “Wow. This is a horror movie.” I sold it as that originally, but I think maybe they thought it was going to be like “horror-lite,” I do think it’s a digestible kind of horror. And their immediate thought was it needed to be a Halloween movie. And that’s been great. They’ve been very supportive of my idea of the movie. I get full approval of the marketing and ads. It’s a pretty great place to be. I think especially The Prodigy does the best job of wrestling out of that targeted audience. I really don’t think you need to be of any kind of proclivities to appreciate what the movie is doing, because I do think the movie is a hard genre movie.

Absolutely. Now, before we go…you’re currently reading “Make Your Own Damn Movie.”

[Omar smiles] I am currently reading “Make Your Own Damn Movie.”

So what is the movie that we can expect from you?

There’s three scripts floating around. Immediately after The Prodigy, and working so hard on this horror movie, there is, I think, a convenience of wanting to make another horror movie, and using these new connections to kind of go into just continuing a horror career. But also it’s always been exciting to me to completely go against what I just did. Are we going to do a light comedy? I’ve been taking notes on a movie about this bisexual woman for a long time, and it’s just cracking a code to get to a place where “let’s stop talking about this movie in theory and start getting dates down.” Let’s start getting actor’s names down, let’s start looking at actor’s reels. That’s where you want to get to, and right now none of these three scripts are there yet. But I’m excited to find out what it’s gonna be when it shows itself.

Photography by Shawn Kelley

Interview by Patrick Peña